Small Point, Maine

Maine was a place of creative magic for John Marin. At the suggestion of his friend, the etcher Ernest Haskell, Marin traveled from his home in New Jersey to Maine for the first time in the summer of 1914. He painted along the coast of West Point, near Phippsburg. As he worked, he fell in love with the New England state. Even grey days of rain and fog enchanted Marin.

Over the years, Marin and his family would gradually shift summering places in Maine north to more and more remote areas. There the artist could work in peace. Marin wrote to his friend and dealer, Alfred Stieglitz, from Stonington, Maine, in 1921, “Glad I am to be away from all the hurly burly I have left behind for a time…. Glad to walk down to the shore and jump in the boat…. Once in a while to paint a picture with none to butt in with another word. To take out my colors with none to say, You should have said pigments?” [John Marin. The Selected Writings of John Marin. Edited by Dorothy Norman (New York: Pellegrini and Cudahy, 1949), 39.]

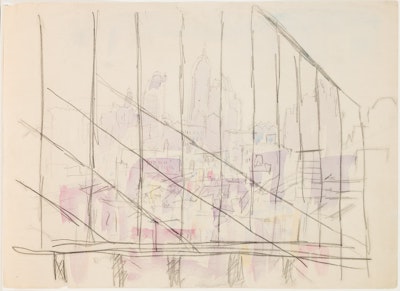

In the wilds of Maine, there was not normally much need for Marin to make quick graphite sketches as he did in New York, where the crowds would not permit him to work undisturbed for long enough to complete a watercolor. Most of his New York Watercolors would have been created in the artist’s studio in Cliffside, New Jersey, where he could work without being stared at and bumped by passersby.

Wonderful, this roaming the woods.

John Marin to Alfred Stieglitz, November 23, 1919

When he was working in Maine, Marin could simply draw on a sheet and then make the watercolor over the drawing. He had all the time in the world to draw and paint.

In his correspondence with Stieglitz, Marin told tales of the grueling conditions he encountered in Maine on his painting trips, coping with swamps, mosquitos, and broken-down boats. He also discussed hours of intense personal reflection and moments of great beauty. Writing in September 1914, the artist declared, “But then I don’t like tame places…. A little bird and its plumage gives the heart a warmy, warmy feeling. Huge waves sounding on a rock-ribbed shore makes the heart, liver, lungs, everything, the whole human critter expand ‘nigh to bustin point.’ Then you live, live, live, and you ‘got to do something.’” [Marin, Letters of John Marin. West Point P.O, Maine, September 16, 1914.]

During the summer of 1915, Marin shifted his summer place to the nearby Small Point. He loved the juxtaposition there of sea and forest.

Small Point, Maine, White Mountains in the Distance 042

John Marin, Small Point, Maine, White Mountains in the Distance, 1915, watercolor over graphite on textured watercolor paper, 16 × 19 in. (40.64 × 48.26 cm.), Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection Gift of Norma B. Marin, New York, New York. 2013.018.022

That same year Marin shocked his dealer and mentor, Alfred Stieglitz, by spending his year’s income to buy an island slightly farther north, off Small Point Harbor. The forested little island proved an impractical place to stay, since it had no source of water, but it was beautiful to paint.

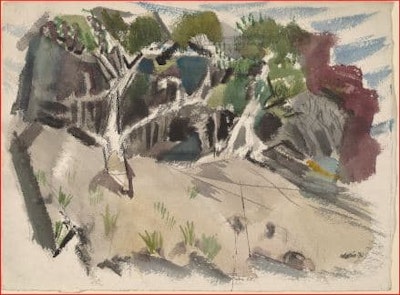

Marin’s watercolors and other places in Maine appeared annually on the walls of Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 on Fifth Avenue in New York City until the gallery closed in 1917. Then they appeared in Stieglitz’s later galleries, a room at Anderson Galleries, and his own The Intimate Gallery, and An American Place. The October 1916 issue of Camera Work, the magazine Alfred Stieglitz produced, described and reproduced critical response to Marin’s latest show there. The exhibition presented a recent group of Maine landscapes, including Rock Shapes and Tree Shapes, Small Point, Maine, the only work in the Arkansas Arts Center’s collection that can be proven to have been exhibited at 291. Critic Henry Tyrrell said of Marin’s compositions, “their piquing mystery is a real spur to our imagination and a pleasant one.” [Henry Tyrrell, “‘291’ exhibitions: 1914 - 1916: Henry Tyrell in the Christian Science Monitor,” Camera Work, October 1916, 21.] In Rock Shapes and Tree Shapes, Marin looked to the example of the French cubist painters, abstracting the view by examining it’s various facets through time as he moved around the place where he was working.

Rock Shapes and Trees Shapes, Small Point, Maine

John Marin, Rock Shapes and Trees Shapes, Small Point, Maine, 1915, watercolor and graphite on textured watercolor paper, 16 ⅜ × 19 ½ in. (41.59 × 49.53 cm.), Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection, Gift of Norma B. Marin, New York, New York. 2013.018.138

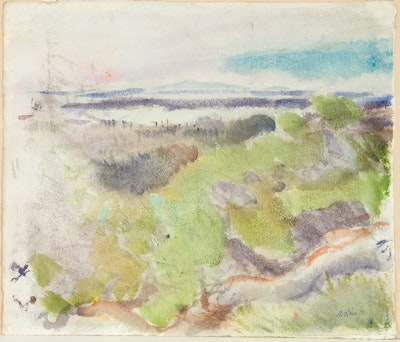

A pine-grown rock outcropping on top of Morse Mountain in Small Point, Maine, became one of John Marin’s favorite places for painting during his early years summering in Maine. He returned to this exact point of view many times. The scrubby pines that clung to the rock became regular characters in the artist’s watercolors.

Took a long hike to a wonderful creek — mountain stream

John Marin letter to Alfred Stieglitz, August 8, 1916

First it must be fished — afterwards painted.

The spectacular point of view from little Morse Mountain includes the rocks and pine trees in the foreground, a stretch of salt marshes in the middle ground, further small mountains in the background, and a beach where breakers crash at the left.

These elements are clearly seen in a recent photograph.

Marin summered in Maine most years for the rest of his life. In 1919, the artist’s summer home base moved north to the little lobstering town of Stonington on Deer Isle. The forests and rocky coasts provided many wonderful subjects to paint.

The artist returned to Small Point often through the years for brief visits to paint there even when his summer home was elsewhere in Maine.

Small Point, Maine(1920)

John Marin, Small Point, Maine, 1920, watercolor and charcoal on textured watercolor paper, 26 ¾ × 21 ¾ in. (67.94 × 55.24 cm.), Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection, Gift of Norma B. Marin. 2013.018.245

Small Point, Maine(1921)

John Marin, Small Point, Maine, 1921, watercolor and charcoal on textured watercolor paper, 14 ½ × 22 ⅜ in. (36.83 × 56.83 cm.), Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection, Gift of Norma B. Marin. 2013.018.024

And now, after looking over my scribbling on various pieces of paper, I think that what I have put down is about what I have wanted to say, the gist of it anyway.

John Marin to Alfred Stieglitz, October 18, 1925

After spending two summers in New Mexico in 1929 and 1930, 1931 and 1932 found Marin and his family returning to spend the two summers in Small Point, Maine.

Marin’s most northerly and final place in Maine was on the shore near Addison at Cape Split. He arrived there in 1933 and bought a house. It would be the summer home to the artist and his family for the rest of their lives. Marin made countless watercolors showing views from their house on the rocky shore looking out toward wind-swept, pine-clad islands.